Women of 150 years ago weren’t that unlike women today. They craved camaraderie and the opportunity to foster friendships through a few hours spent together, chatting, swapping advice, sharing compassion and (probably) complaining about spouses. We have book clubs and laugh-filled conversations over a glass (or two) of wine. They had sewing sessions. The ladies who made the original Mt. Ida quilt, a historic textile in the collection of the Alabama Department of Archives and History, did so as a group, and the connections they formed with every stitch sustained them. The ladies who recently made a replica of that quilt discovered their stories and pieced together the same fellowship through common purpose.

[dropcap letter=”I”]t started with Sarah Bliss Wright, who grew up in the Mt. Ida community that’s right outside of Talladega, AL, was looking for a creative outlet after retiring from a life of opera singing and community theatre performances in Mobile. While looking over some handed-down quilts she had, she had a thought. “Like most in the South, I had lots of quilts in the closet, and I thought, ‘Why not give that a try?’” When her father passed, she decided to make a crazy quilt out of his old silk neckties. “That project deepened my interest, but as much in the study of it and its history than the actual process itself,” she said. She got into the scholarship side of quilting and joined the American Quilt Study Group, a national organization devoted to researching quilting’s heritage.

Each year, the group issues a challenge to its members, calling onthem to make a quilt in a specific period or style. The purpose is to encourage modern quilters to learn not just a technique or pattern from yesterday, but to learn about the quilters who first used them or popularized them. “The theme a few years ago was ‘Quilts of the Civil War.’ I knew there must be tons of them here in Alabama,” Wright said. She did some digging and found out about the Mt. Ida quilt, a floral quilt made by 12 ladies who lived on the lands that made up the Mt. Ida community clustered around Mt. Ida plantation. “It was at the state archives, and they knew where it had been made, in the same area I grew up in, and that it was made for a wedding, and they knew the names of its 12 quilters, but they didn’t know much about any of them.”

A light bulb clicked on. “I decided to gather 11 other women who still lived in that area, on the land the original quilters did, get each to ‘adopt’ a square of the original quilt, and we’d work on it together for the challenge,” she said. It was a great idea, but she needed the others to sign on, and some of the ladies might not even know how to quilt. “Actually, none of them did,” Wright said. She had called 11 women, ranging in age from late 30s to mid 80s, to participate, and despite their lack of quilting know-how, they all said “yes.” “It was a funny thing, since they weren’t quilters, but they wanted to see what we might uncover about the people who lived on the land before them.” The old plantation lands had only changed hands three or four times in the more than 160 years since the first quilt, so many of the women already felt a kinship to the original quilters.

A light bulb clicked on. “I decided to gather 11 other women who still lived in that area, on the land the original quilters did, get each to ‘adopt’ a square of the original quilt, and we’d work on it together for the challenge,” she said. It was a great idea, but she needed the others to sign on, and some of the ladies might not even know how to quilt. “Actually, none of them did,” Wright said. She had called 11 women, ranging in age from late 30s to mid 80s, to participate, and despite their lack of quilting know-how, they all said “yes.” “It was a funny thing, since they weren’t quilters, but they wanted to see what we might uncover about the people who lived on the land before them.” The old plantation lands had only changed hands three or four times in the more than 160 years since the first quilt, so many of the women already felt a kinship to the original quilters.

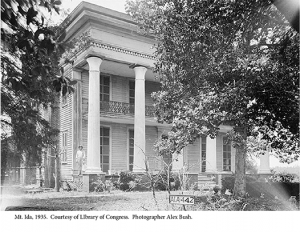

They added a 13th member, who didn’t make a square but served as an advisor and helped with the quilt stitching, and they started in January 2013, meeting every six weeks to work together. They learned that the quilters were wealthy white women of the Welch and Mallory families, two of the families that settled in the area in the 1830s after leaving Virginia, and that their families got wealthier still coaxing cotton from the fertile soil. They found out that the original quilt got its name from where it was found, the Mt. Ida house, the largest and grandest of the plantation homes in the area, which was also home to one of the quilters. The group also learned of the difficulties the ladies who’d come long before them faced, despite an outward appearance of luxury. “We know that they faced challenges that were to us, insurmountable, the loss of children, multiple children,” Wright said. “The health issues they faced and so many other things, were greater than what most of us deal with today. But you see parallels too. They wanted so much for their children; we all want that too.”

Wright and her group became closer through the process as well. “We all knew each other, waved at each other from our air-conditioned cars, but we didn’t take the time to sit and really talk,” she said. “We began to see a sense of community in that one of us would help out someone else lagging behind or someone having trouble with a technique.” They met in each other’s homes just as it’s believed the original quilters did. “We’d have coffee and tea,” Wright said. “We’d quilt some and visit some.” As their comfort level increased, so did their connection, and not just to each other. “We became more aware of our other neighbors and what was going on with them. That is something sorely missing in our world today.”

When the quilt was done, out of 50 works in the Study Group’s challenge, it was one of the 25 picked to tour the nation. “It was much more than just a replication of technique,” Wright said. She and her group told an old story and wove a new one. They’ve stayed in contact and see each other as often as possible. And they may soon embark on another project. “We keep looking for something else to do together,” Wright said. “Stay tuned.”

Written by Jennifer Kornegay / Photos Courtesy of Sarah Bliss Wright

SaveSave

SaveSave