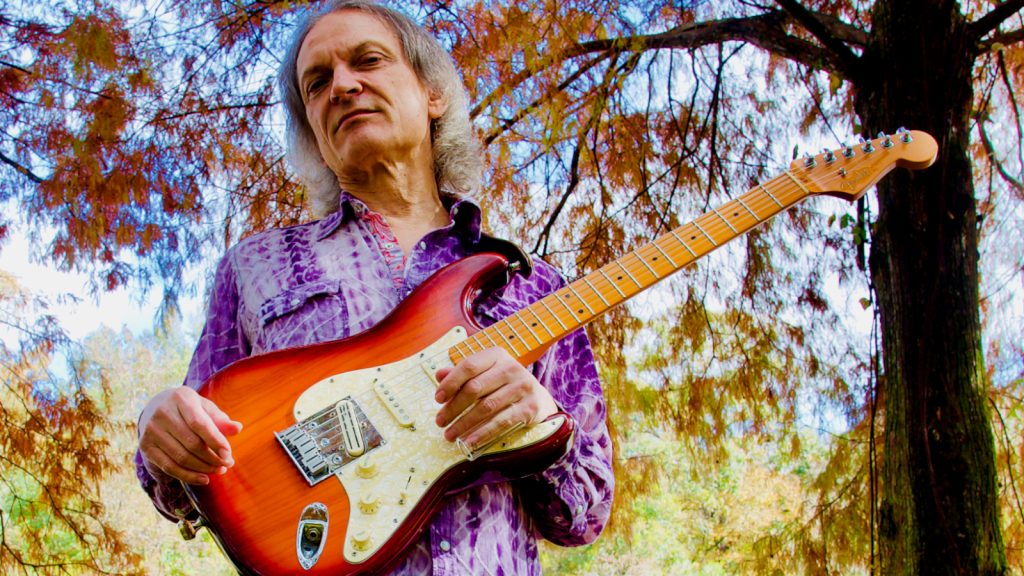

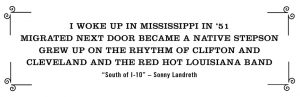

Sonny Landreth plays a mean slide guitar. From his humble beginnings in Mississippi to stages around the world, he has managed to stay grounded, his roots firmly set in the South. Oddly enough, his first instrument was the trumpet, guitar came later.

Guitar was my first love.” Landreth is on the phone from Lafayette, Louisiana. He sounds relaxed and in the mood for a good conversation. “I was born in Canton, Mississippi. We moved to Jackson for a bit, and then to Lafayette about the time I entered second grade.” It was his older brother Steve who first influenced him. “He would bring records home. He played trumpet. I started out playing trumpet because of him, when I was around ten-years-old. But guitar was my first love. My folks caved when I was thirteen and then I had a trumpet and a guitar. The trumpet was my academic instrument, the one that I played in school.”

It was the horn that informed his approach to guitar, especially slide guitar. “I love the lyricism I found in playing slide. I got that from jazz. Delta blues are story songs, and the slide works with the lyrics in a sort of call and response fashion.”

As a young man Landreth soaked up the musical atmosphere of the day. “At that time Elvis was really all the rage. I started listening to these jazz cats, and went to New Orleans. The twist became the big thing, Chubby Checker. I became enamored of B.B. King.” He found inspiration in the music of Al Hirt and Pete Fountain. “And Ellington, and the second line stuff.”

Landreth was fourteen when he played his first gig. “My friend Tommy and I started a band. We were still learning how to play. My folks worked for State Farm insurance and they used to have parties with other agents. We knew six songs and played them over and over. I think what they did, was they paid us to stop playing. We each made five bucks and I didn’t have to mow the lawn!”

Today Sonny Landreth is revered as a slide guitar virtuoso, often appearing at Eric Clapton’s Crossroads Festival. Approaching the guitar as a wind instrument player shaped his phrasing. “Your phrasing becomes centered on taking a breath. It’s an entirely different mindset.” He also counts Chet Atkins, Jose Feliciano, Buck Owens and Johnny Cash as making an impact on his style.

Yet Landreth doesn’t sound like them, or anyone else for that matter. He can hit you with a buzz saw lick one moment and make the guitar shimmer with an ethereal tone that floats off the fretboard the next. He draws effortlessly from the culture of Louisiana.

“I heard Clifton Chenier, the Zydeco King, at the Creole Club. I was deep in the blues and a friend told me about a guy who played the blues on accordion. I couldn’t imagine that. I met Clifton when I was sixteen or seventeen. Later, I heard B.B. King in New Iberia, and saw Hendrix in Baton Rouge. I met Hendrix, all of this within the period of eighteen months. Growing up down here – it’s such a rich culture.”

As time passed Landreth began to jam with other musicians and play local gigs. “One night Clifton came to a place where I was playing. He sat by my speaker cabinet. After that night he asked me to join the Red Hot Louisiana Band. It was my introduction to Creole culture. I played with him off and on for about three years. In between I played with Zachary Richard.”

Landreth loves to discuss the way music connects people. “You play a gig and you never know who is going to be there. Maybe that person can’t help you on your journey, but they know someone who can. That’s what makes it rewarding. One thing leads to another.

“I was in Austin doing studio work for Ray Benson of Asleep at the Wheel. Benson told me John Hiatt was auditioning band members. The next thing I know Benson hands me the phone. Hiatt is on the other end. So the next day Benson gets me on a plane to Nashville. I do the audition and get the job. Hiatt gives me a copy of the album Bring the Family. I get back to Louisiana and I’m listening to the record and there is such a kindred spirit in the songwriting. It’s raw and honest. So I did something out of the ordinary. I called Hiatt and told him I knew who he needed for the band. Hiatt flew Dave Ranson and Kenneth Blevins and me to Nashville. We played one song and Hiatt cancelled all the other auditions. That is how The Goners were born.”

John Hiatt and the Goners went on to record three albums together. Since then Landreth has stayed quite busy. In January he will release his fourteenth album, as yet untitled. “I have a working title, but I won’t say it, in case I change my mind.”

Landreth has been in demand as a session player and is a regular at blues and rock festivals. Eric Clapton has praised him for his technique. Along the way he has collaborated with the likes of Mark Knopfler, Derek Trucks, and John Mayall, to name a few. His songs have been covered by other artists, most notably the song Congo Square.

It’s quite a ways from the early days of playing his parent’s parties. What is it that makes music from the south so memorable? Landreth chuckles. “I don’t know if it’s the humidity or the gumbo. You heat it up and the (spices) float to the top.”

Written by Joseph M. McSpadden / Photography by Bruce Schultz