For one Texas woman, inheriting family quilts inspired a journey to repair,

restore and conserve this legacy for another hundred years.

Written by Sarah Durst / Photography Lena Seaborn

Additional Photography Courtesy of Sue Ann Goodman

When Alabama really quilted, the winters were colder. That’s not true, though, and you know it, as well as I. Alabama has never been cold. But Alabama did quilt a whole lot more than it does nowadays. Back then, it was a necessity. Now, quilters do it for pure joy, showmanship, and love of the craft. Quilting today is no less beautiful, no less complicated; completed with no less skill – but it doesn’t bear the weight of drafty walls or worn-out ticking mattresses stuffed with hay or sweet grass. While it was born of necessity, it was also art: a woman’s craft on display in the patchwork folds of feed sack fabrics and scraps from old clothes.

Many of these quilts have been lost to history. As an avid quilt collector, coat maker, and quilt dealer myself, I have seen the quilt market dip, soar, and rise again in the past 15 years. It used to be quite easy to stumble across a pristine 1880’s Mariner’s Compass or Bear Paw in antique shops across the country. Now, those pieces are few and far between. What’s more, one used to be able to find quilts with signatures or little pieces of paper that told a brief history of the quilt itself. But most of those have been lost to time. And while occasionally you might find one or two quilts from the same household, you would be hard-pressed to find thirty and certainly never thirty from the same family.

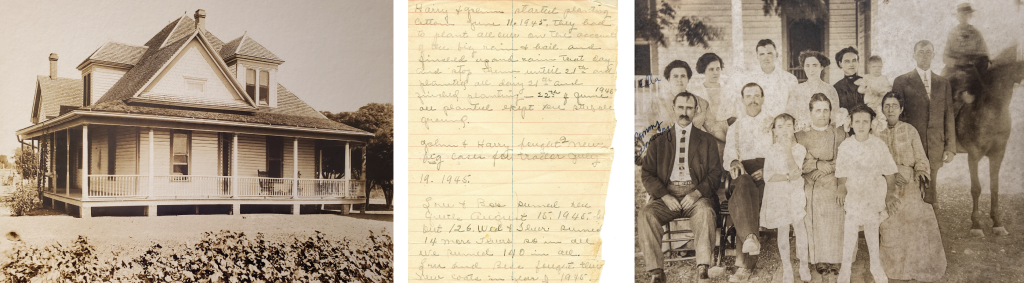

The sheer quantity alone makes The Orr Family Quilts a once-in-a-lifetime collection. Couple that with the family’s ephemera – notes and diaries listing out details and insight into the care of the quilts – and you have a Smithsonian-level quilt exhibit currently making its home in rural Texas. The story of the Orr family quilts starts in Alabama in the 1840s. It began in a small place called Silver Run, where one woman wove a story in patchwork and thread that would wend its way down through time and speak to all who might listen a hundred and fifty years in the future.

In 1975, when the last of her great aunties died, Sue Ann Goodman’s mother Mable was tasked with dividing the estate amongst relatives. As Mable climbed the stairs to the second story of the old family farmhouse, she found over 120 quilts piled neatly on an old iron bed frame. The family divided them up and Sue Ann found herself in possession of 20 of these treasures. After Mable passed away in 2019, Sue Ann inherited 14 more quilts. Unsure of what to do with this vast quantity of quilts, but sure that something should be done with them, Sue Ann had the quilts appraised. She was shocked to learn that some of the quilts dated to the 1870s. From there, the idea began to form in her mind that she must work to conserve and restore the quilts thereby preserving the legacy of the Orr Family Quilts.

Sue Ann’s family quilt history began with Lucinda Morgan Orr. Born in Jackson County, Georgia, Lucinda married John Christopher Columbus Orr in 1840. In the mid-1840s, the family moved to rural Silver Run, Alabama. Lucinda was an accomplished quilter and spent a great deal of time making quilts, preserving, and saving each and every fabric scrap from store-bought linens to worn-out family clothing. Lucinda and John’s daughters, Ovelia and Rianna, carried on the quilting tradition, along with their sister-in-law, Maggie Nicks Orr. In 1898, the Orr family moved from Silver Run to Brandon, Texas. Rounding out the third generation of quilters were Maggie’s three daughters Margaret Ava Orr Potter, Katie Lou Orr, and Bessie Mae Orr. These women would work together in their sitting room piecing blocks. When they placed them on the floor to join them, they often fit together perfectly, even though they were made by four sets of hands. These women worked together to carry on the quilting tradition and took up the care of the vast quantity of Orr quilts. Several cards and journal entries saved across the generations mention family members airing out and sunning the quilts, a tradition that continued well into the 1950s, when Sue Ann was a child and could participate herself. Margaret Ava’s daughters Nora Elizabeth Potter Sims and Mable Olivia Potter Goodman were the fourth generation of quilters and Sue Ann, the fifth.

So it was that Sue Ann’s journey to save and repair her family’s quilts began. As Sue Ann put it, “I went on a mission to fix them up – to make them as good as they could possibly be for their next 100 years.” What was especially tricky for Sue Ann was finding fabric that was from the same time period as the quilts. Sue Ann found out that if you went to any modern fabric store and bought new fabric and placed it on the old quilt, the quilt’s antique value would be ruined. As she began working on the first quilt, the Bricks, she knew that some of the blocks were made from her great uncle’s denim trousers and her auntie’s old house dresses and smocks. After trying to buy old work shirts online (they weren’t even close to a match), Sue Ann happened to talk to her brother, James Goodman, who was still in possession of a few of the quilts. After looking through the pictures James sent, Sue Ann quickly realized that the fabrics in her brother’s quilt were a definite match for the one she was working to restore.

The next day Sue Ann drove to James’s house to inspect the quilts in person. Luckily, he was amenable to the project at hand. Sue Ann took the quilts home and immediately began the work of deconstructing one quilt to have matching fabric to repair the other. As she slowly worked to undo the seams of the quilt James owned, rather than finding cotton batting in the middle of the quilt, Sue Ann found a second quilt. That’s right – hidden inside one quilt was another. The hidden quilt was made of fabrics from the 1910s and 1920s rather than the 1930s and 40s fabrics of the exterior quilt. Sue Ann was thrilled with this discovery. Using these two quilts, Sue Ann found authentic, period-correct fabrics to begin the task of restoring and repairing all of the Orr family quilts in her possession.

As the months went on, Sue Ann was surprised to find more of these hidden quilts-within-quilts. This practice was not uncommon. Throughout quilting history, avid quilters would use quilts that were wearing thin as the batting for new quilts. Sometimes these secret quilts are found because the new quilt feels quite a bit heavier than a quilt should be. Often times, the quilt that is hiding can affect the color of the exterior quilt. For example, there might be a purple hue to blue fabrics suggesting that a red quilt exists underneath. Most commonly, the outside quilt begins to wear, showing bits of other fabric and quilting underneath. In Sue Ann’s case, these quilts-within-quilts were treasure troves of authentic fabrics that served as the building blocks of her repair work. But these hidden treasures also spoke of her family’s ingenuity – their desire to let nothing go to waste and preserve that which they could. It was a trait Sue Ann certainly knew something about.

This ingenuity was also on display through the family’s repeated use of fabrics. Another way quilters would “make-do” was to reuse fabric, sometimes over and over again in new quilts. Sue Ann shared that one quilt in particular, “Three in the Corner,” is made of fabrics that span sixty years from the 1880s through the 1940s. “It’s not that my family worked on the quilt for 60 years. The family had a big giant trunk that was filled with fabric scraps.” As the Orr quilters would get an idea, they would dive headlong into the trunk finding turkey reds and cheddars from the 1880s, indigo calicos from the 1890s, and then more recent shirting or cotton fabrics from the 1930s and 1940s. It was not uncommon for Sue Ann to find the same fabrics pieced in ever-decreasing sizes across the Orr quilts.

Sue Ann was gifted the trunk of fabric scraps in the early 1970s and used some of the fabrics to make her own quilt. It was a simple block quilt, but she was proud of it. She took the quilt to the nursing home so that her Auntie Katie Lou Orr could see her creation. Sue Ann was sure that she would be proud to see the family tradition being carried on. Auntie Katie Lou took a look at Sue Ann’s work and said, “Now honey, you always want the seams to hit.” She was, Sue Ann noted, her teacher until the very end.

The Orr quilts are perfect examples of Deep South utilitarian quilting. While they may not be the best example of fine quilt stitching (sometimes only 6-7 stitches per inch), the piecing is quite extraordinary. After the fabrics were meticulously chosen from the trunk of scraps, the Orr quilters would cut the pieces, and hand-baste them together before combining the quilt with whatever batting they opted to use. Joyce Larson, the first appraiser for the quilts, was amazed that the quilts used wool batting given the availability of cotton in Alabama. However, in her book, Historic Tales of Talladega, Grace Jemison wrote of two wool carding mills producing yarn and batts in the Choccolocco Valley near the Orr family farm at Silver Run in Talladega County. So, Lucinda Orr would have had access to wool batts. Later, Maggie and her family carded their own batts from their annual cotton crop once the family migrated to Brandon.

After the batting was chosen the quilt backing was added (usually made from a chintz or with feed sacks) and quilted. Most of the quilt backings were made with runs of yardage from one bolt of fabric. All but a few of the backs were machine stitched. This suggests that a sewing machine was likely in the family in the 1880s, a time when this would have been quite uncommon. The quilting itself would take place over several weeks with family members contributing to the rows and rows of stitches that traipse across the surface of the quilt. Lastly, the quilt was bound, either by using a separate binding or by taking the backing of the quilt, wrapping it around to the front and stitching it in place with a simple whip stitch. The expertise that the Orr women used when creating the quilts certainly made Sue Ann’s restoration work easier. There was no wonky quilting or loose block seams. Sue Ann did not need to work to correct shoddy craftsmanship, but rather she had to contend with the natural decline of the fabrics over time. The fact that the quilts were made and cared for so well ensured their ability to withstand use over the years.

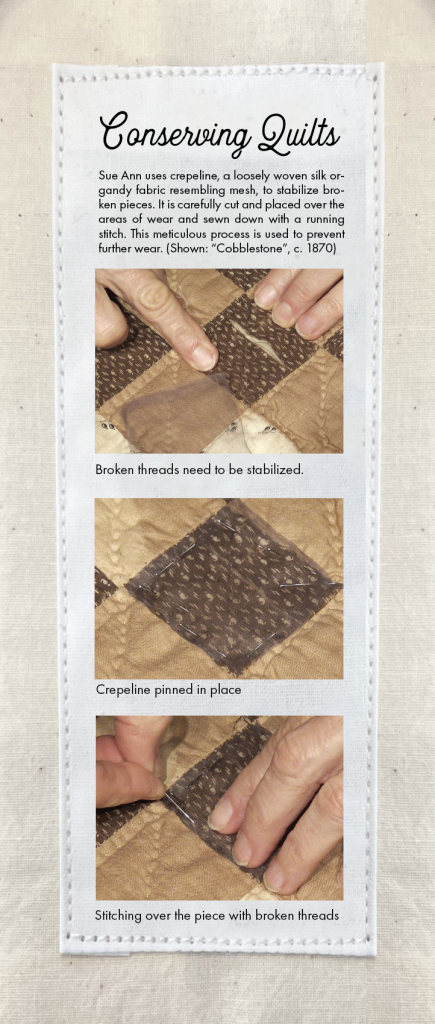

As Sue Ann continued working on the quilts, she noted that not every quilt needed as extensive repairs as the Bricks quilt. Some of the earliest quilts, “Flower with Leaves and Buds” and “Wandering Jew” had very little wear or problems despite being from the 1870s (or even earlier in the case of the floral applique). Sue Ann noted, “It is impossible to find fabrics from the 1870s, so I used crepeline to fix the areas of wear.” Crepeline is a loosely woven silk organdy fabric that resembles mesh. The crepeline was carefully cut and placed over the areas of wear and sewn down with a running stitch. This meticulous process worked to conserve the quilt and prevent further wear.

And while each quilt in the Orr family group had its own needs for repair, Sue Ann also found that each quilt carried something else with it as well. Sue Ann has had several appraisers work with her over the years. During one session, the appraiser looked at a particular quilt and said, “Oh that’s a happy little quilt!” Sue Ann was intrigued. “How could a quilt be happy,” she wondered. But as she began to work with each quilt, she began to understand what the appraiser meant. Most of the quilts she spent time with were happy quilts. No matter the colors, the quilts carried with them the joy of the makers – and Sue Ann could sense it. She noted that it seemed as though she was wrapped in the care of her family while working on these quilts. Sue Ann did sense that there was one that was different from all of the others. “The Cobblestone quilt,” she mentioned, “that was the last one I worked on. That quilt was not happy. When I worked on it, I kept feeling kind of weighted down and melancholy.”

This quilt was attributed to Lucina Morgan Orr, the first quilter in the family. It was most likely made in Silver Run, Alabama. As Sue Ann learned more about her family’s history, she discovered that Lucinda endured deep hardship and losses that were common to the time period. Over the course of her adult life, Lucinda outlived five of her eight children and three of her grandchildren. It is probable that the Cobblestone quilt was made during a time of deep sorrow in Lucinda’s life. Perhaps it was pieced together following the death of someone she loved dearly. Perhaps it was quilted as Lucinda worked through and carried her grief. Regardless, Sue Ann found it to be true that every quilt carries with it the weight of the lives lived and the lives gone from underneath its threads.

Now that Sue Ann’s work is completed, the question remains, “What is to become of the quilts?” As designer, quiltmaker, and author Flavin Glover noted, “[Sue Anne’s project] is a significant, thorough, and authentic family history project that effectively stitches together written words, photographs, genealogy, and quilts.” Sue Ann is the last in the line of quilters, with no one ready to take them up again. And this is the way of things, I suppose. All of our material possessions become imbued with meaning to those of us among the living. We care for them, we teach others about them, but when we are gone it is up to those who remain to carry on. Sue Ann hopes that there is a place for the Orr Family quilts and their story: a story of five generations of quilts and family, threaded together across time. For now, she is content that they live with her and that she can share her family’s story and legacy with any who might care to listen.